This article was originally published in the Fall 1991 edition of the Goldenseal Magazine. It is published here with their permission and our special thanks.

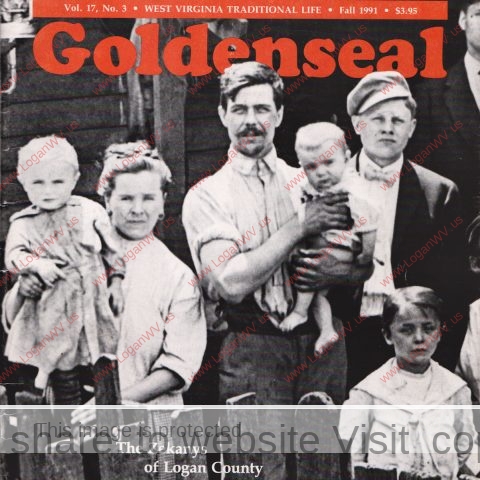

Grandma and Grandpa Zekany

Growing Up Hungarian in Logan County

By Donna Jean Rittenhouse

Donna Jean Rittenhouse grew up largely in the Logan County household of her Hungarian-born grandparents, Alexander and Elizabeth Zekany. She routinely spoke Hungarian in their presence, and absorbed many of their native customs. Today she remembers the immigrant couple with respect and affection, recalling their guidance to her as well as the help she gave them in understanding the English language and comprehending the ways of their new American home. – ed.

My first memories of life are of the house in Henlawson where I was born. Everyone called it the boarding-house, although I can only remember there being two boarders in my time. Henlawson is in Logan County, just north of Logan town.

I can remember Grandma teaching me the Lord’s Prayer and the Apostles’ Creed in Hungarian. Every night, no matter how early I went to bed, when Grandma herself was ready to go to bed I was awakened and urged to kneel in my bed and say my nightly prayers. Grandma would stand by the bed with her hands clasped at her breast and help me out.

Even when I was old enough to say them through without a mistake, Grandma still stood by the bed in case I needed help. Or was in to make sure I didn’t nod off? I can remember doing that at times, then my eyes popping open and my head snapping up as she would prompt me with the next words. After prayers were done, she would tuck me in snug under my plump feather-bed comforter.

I always knew if I couldn’t find Grandma anywhere in the house, I could find her in the garden. It was a very big garden, out past the backyard, past Grandpa’s workshop near the chicken house. Grandma worked in her garden every day during the spring, summer and fall, planting vegetables and tending her rose bushes, which enclosed one long side next to the road and the farthest end. I was always threatening my friends when they wanted to pick even one of Grandma’s roses from the outside of the fence. I don’t know why, because there were thousands of them.

If Grandma wasn’t in the back garden, she was in the front yard. She had many different kinds of flowers growing along the fence, in circles with stones around them. She would pick grapes for grape juice from the grape vines which Grandpa planted in the opposite side of the yard.

Grandpa had also planted an apple tree and a peach tree at the farthest end of the garden. He had planted a mulberry tree in front of the chicken yard. It was enormous by the time I was old enough to climb it. There were a couple of limbs that made perfect seats just where they jutted out from the trunk. This was my hideout, and I would share it with my friends.

Grandma and grandpa demanded that I stay off that tree because I might fall out. When caught up there I was threatened with the strap. I cannot remember ever getting the strap, but I certainly knew about it! It was made of a strip of brown leather about a foot long and about half an inch wide, attached to a smoothly rounded wooden stick with just about the same dimensions. It hung on a nail on the kitchen wall.

I can remember coming into the house from playing late with my friends. Grandma stood waiting for me. She held the screen door open with one hand but had the other behind her back. I would not budge until she promised not to whip me. Then I would run past her, looking back to see if she really did have the strap. She always did! I don’t know why she always held the strap but never used it. Probably just to make me believe that he meant business, but I knew I could trust her “Nem.” Later on I came to know that neither she nor Grandpa would every have laid a finger on me.

Every evening I would watch for Grandpa to come walking up the railroad track, coming home from work at the coal mines. I would run to me him and he would pick me up and carry me the rest of the way. When we go home he would go take his bath.

When we had all had dinner, sometimes we would go out and sit on the front porch until after dark. Grandma and Grandpa would talk. I would lay in the swing with my head in Grandma’s lap. Grandpa would sit in a chair. I would look up the hollow from the porch, look at the sky above the mountains and wonder what was on the other side of those mountains. A few years later I came to know that there were one or two other families that lived on up the hollow from us and our neighbors. I also came to know that the coal mines were farther up the hollow from up. I still don’t know what is on the other side of those mountains.

Every time it would thunder – an oncoming rainstorm or one already in progress – I would run and hide my head in Grandma’s lap. I would shake with fright and cry “I’m scared!” She would lay her hand on my head and advise me, “Then shiver.” (We both spoke in Hungarian, of course.) I know what she would say, but I would still run to her. Her hand on my head was always more of a comfort than her joking advice.

In the winter when we couldn’t go outside to sit on the porch, Grandma and Grandpa would sit in the middle room in front of the fireplace. Sometimes we, Grandpa usually, would have company. Sometimes (let’s see how close I can come to spelling this correctly) Jynosh Bychy would come and stay a couple of days. He was a family friend. I don’t remember if I ever really knew what his work was. I believe Grandma told me he was a traveling salesman, but I can’t remember him selling anything to Grandma or Grandpa. Maybe he never came to sell his friends anything, or maybe his wares were too Americanized.

Grandpa would always sit in his chair, a wooden chair with square legs. He had made that chair, as he had several other pieces of furniture in the house. Every day after work he would sit in that chair to remove his work clothes, and he would put on his socks and shoes there each morning. Anyway, it was his chair. It stood with its back against the stairway which led to the second floor.

That chair caused the only argument that I can remember Grandma and Grandpa every having. One day Mrs. Demetroff and her two daughters, Helen and Irene, both older than me, were visiting. The two women were in the kitchen talking, while Helen, Irene and I were in the middle room. We started to play, Helen and Irene chased me around and around the table.

Of course, the “bound-to-happen” happened. I tripped and fell, hitting the left side of my forehead on the corner of one of the square legs of Grandpa’s chair. With my screaming and the blood and with Mrs. Demetroff yelling, I guess Grandma saw this as the of me. When Grandpa came home from the mines, he ran smack into her wrath. She wanted his dangerous chair out of the house! Grandpa calmed her down, maybe by saying that I had learned why I had been told so often not to run in the house. The chair stayed where it was, Grandma said no more about it, and I never ran in the house again – not too fast, anyway.

Sometimes when Grandpa sat in his chair in the evenings talking, I would crawl into his lap. I would sit with my head against his chest. I remember listening to his heart beat. His voice rumbling down in his chest. I would look sideways up at his neck and watch his Adam’s apple move up and down. Sometimes I would fall asleep there in his lap.

And some night I would try to stay awake until after twelve midnight. My friends had told me that ghosts came out then. They had done a good job of explaining that fact to me, and I wanted to see one.

I had two conceptions of what ghost were. There were ghost which were dead people and bad at that, who could come back to hurt you. There were other ghosts, or good spirits, who could come back, too. I knew all that for a fact because Grandpa would put bread and salt on the table on All Saints Eve before we went to bed. I don’t remember exactly what it signified, but a rational guess is that the spirits awoke and roamed on that special night.

Speaking of ghosts and spirits, Grandpa had the house blessed. I can remember it taking place only once. The priest came and Grandma, Grandpa and I followed him from room to room, downstairs and upstairs, while he sprinkled holy water around. I don’t know where the priest came from, probably Logan. I know there wasn’t any Russian Orthodox Church in Henlawson.

When Grandpa went to town, I used to wait impatiently for him to come home. When he finally did, I would always ask if he had brought me any candy. Sweets were a real rarity in my childhood at Henlawson. We had good and nourishing food, but candy, pop, and “American bread” – as Grandma called white, sliced bread, since she always made home baked bread – were rare. Grandpa would always have lemon drops in his breast pocket for me.

One day I came home from playing at the Demetroffs and found Grandma down in the cellar with a man in a business suit. I went downstairs and heard him asking Grandma a lot of questions. He complimented her on all of her canned foods, and after a while he left. It had been reported that Grandma was hoarding store-bought food! It was during World War II and that was against the law. We could not think of who would have turned her in for hoarding, when, in fact, she wasn’t.

Grandma used to take fertilized eggs upstairs into the warm extra bedroom and lay them all out on top of newspapers to hatch. That kept them from being killed by the other chickens before they were hatched. I have seen eggs cracked open by chickens, so I guess some chickens like raw eggs. At any rate, I used to go upstairs and check on the chicken as they hatched. I would play with them before they got old enough for Grandma to put them back outside in the chicken yard — but still away from the older ones.

Grandpa’s workshop was really an out-of-doors blacksmith shop. When he was out there making tools for himself or horseshoe for someone, I would sometimes go out to watch him. He would have me turn the handle of the bellows. That would blow air under the fire into which he put the iron he was working on. Then he would put the item on the anvil and hammer or “forge” it into shape. I was always afraid of getting burned by the sparks flying from his hammer.

One day I had the opportunity to watch Grandpa shoe a horse. I remember being very surprised that he could do this. After that, I was confused about Grandpa’s work as blacksmith for the mines. I didn’t know that they had horses at the mines and I still don’t know if they did or not. I found out later that mostly he made the tools, or a least the special ones, that they needed, and repaired the broken ones.

I remember two winters that we slaughtered pigs at Henlawson. Several men came to help. It took place out in the back side of the garden where there were no plantings, where the big rocks led up to the railroad. Grandpa would send me away before the throat cutting. I found out in later years that that the reason the pig squealed so loudly and then stopped so quickly. But I never thought about that when Grandma made the stuffed sausages, the crisp pork fat, and the jellied pig’s feet – or koládz, pattogás, and kocsonya, respectively, as we referred to them in Hungarian. She worked from early in the morning until late at night.

It was explained to me at an early age that if I stayed out late, the “boogerman” would get me. He would come walking up the railroad just after dark, with a sack on his back into which he put children to take home to eat. And to top it off, which I guess was supposed to make it more scary, he was a black man. For years I was really fearful at being outside after dark, even in the yard, even in the company of Grandma or Grandpa. I sure didn’t want the boogerman to get me.

Then one evening when Grandma, Grandpa and I sat on the front porch talking, the boogerman came walking. I knew it was the boogerman because he was a black man and he had a sack thrown over his shoulder. Anyway, he saw us sitting on the porch and spoke to us. Grandpa got up from his seat and walked right over the fence. The boogerman stopped and they talked together! It was dark by the Grandpa bade the boogerman goodnight. When I asked, he explained to me that this a nice old man with whom he was acquainted. He lived on up the hollow, and he wouldn’t hurt anyone. I never was afraid of that particular boogerman again.

My mom was postmistress at the Henlawson post office. At times when I stayed at Grandma and Grandpa’s, she would come up to have lunch with me, as often as possible. When we finished lunch, I would run to the door and stand with my back against the kitchen door and my arms flung wide so that Mom could not leave again. Grandma would have to pull me away and hold me so that Mom could leave, me fighting her and crying as if my heart would break. When she let go, I would run to the middle room and out the door and over to the outside of the washroom wall where I could look through the wire fence and see Mom walking down the railroad tracks, heading back to work.

When I was old enough I would go to the Dunches to play with Paul, who was my age, and Violet, who was a couple of years older. And they would come to see me when Mrs. Dunch came to visit Grandma. Once Mrs. Dunch told Grandma about Paul, Violet and me walking across the Henlawson railroad bridge, not on the walkway but across on the railroad trestle side. We could see right down between the ties and into the river. We could have slipped between them, down into the water. When I got home Grandma was standing in the door, holding the screen door open with one hand – and the other hand behind her back. She let me know in no uncertain term I was in trouble.

After I got older, I made the trip by myself and always took the walkway side of the bridge. But I have had nightmares of walking the bridge, on the correct side, when it begins to tip and I slip off in the river. At first I can hold my breath and see underwater. When I can hold it no longer and take a big, deep breath, I wake up. I have had the same dream many times.

On cold winter mornings, when Grandma got me up to get ready to go to the Midelburg Addition school, which was quite a walk, she would have a roaring fire in the kitchen stove. She would have the oven door open with a kitchen chair pulled up in front of it. I’d come out wrapped up in a cover. She would have a hot cup of coffee ready for me. My coffee (as I found out later) was mostly milk, with enough sugar to make it nice and sweet and just enough coffee to make me think that I was drinking coffee like Grandma. It was perfect, I still cannot drink coffee black.

Once or twice I watched as Grandpa sharpened knives and axes on his grinding stone. He would sit on the seat and pedal, and the big round stone would go around. Sparks would fly. When he asked if I wanted to pedal I was always afraid to do so, because I was afraid of the sparks. He assured me that they did not burn, but I was still afraid. He would do this job outside in the back yard.

I used to beg Grandma to tell me stories. The one that has stayed in my mind all of these years was one that her mother told her. It took place in Hungary, of course, and it was scary. It was about a beautiful girl who fell in love with a handsome young man. He convinced her to go to his home with him. The went down into a dark place where she noticed that he had cloven hooves for feet. It turned out that he was a vampire, but she escaped at sunup at the sound of the cock’s crow. It loses something in the translation, but it was scary then and it was the one I wanted to hear over and over.

Grandpa used to try to teach me Hungarian songs. We would sing together at the kitchen table after our Sunday dinner. The one I remember most was (in English) “Wooden Fork, Wooden Spoon, Wooden Dish” – or “Fa Villa, Fa Kalán, Fa Tál.”

My mouth waters when I remember coming home to the smell of Grandma’s cabbage rolls cooking on the stove. I also loved the Sunday dinners. Cooked chicken, with whole potatoes and carrots, quartered cabbage heads and noodles cooked in the chicken broth. I would watch Grandma make homemade egg noodles and pinch small pieces of dough into soup to make tiny dumplings. She used to get upset with me when I added catsup to the soup.

Grandma would sit for hours and crochet. She tried so many times to get me to come and watch her and learn. But I was too busy and, truthfully, not interested. I did learn to crochet a chain. That helped me in my adult life, to learn to crochet fashions or anything that I wanted. I still will not crochet doilies or anything that is not a challenge, but crocheting was her second life.

I remember Grandma combing her hair. When she took out the hair pins and let her hair down, it came down to her buttocks. She would comb it by bringing it over her shoulder. Then she would either braid it or leave it brushed out and then it into a bun on the top of her head.

It dawned on me after many years that when I walked into a room where Grandma would be standing with her hands folded at her breast that she was saying her prayers. Then I realized why she wouldn’t answer my questions and turned her back to me until she was finished. I would stop and go back to the other room until she came in, and then I would say what I had to say.

Sometime I read or translated for the older people around me. Grandpa subscribed to the National Geographic magazine. Grandma loved to look at the beautiful color pictures. She would ask me what the caption said under a picture that interested her.

On evening after Grandpa had come home from work he was sitting at the kitchen table telling Grandma about some young guy at work yelling about something or other. Grandpa said that he turned to and (in English) had called him a ______– a terrible name. I was shocked and asked Grandpa if he knew what that meant. He said it just an expression that everyone used at work. I explained as well as I could what it meant and for him never to say words that he didn’t know just because everyone else did. He was embarrassed and promised he wouldn’t.

One day a neighbor came to visit Grandma and said that her husband had beaten her up for the last time, and she was going to court to divorce him. She couldn’t speak English and needed an interpreter. Her daughter, a year older than me, wouldn’t go with her. Grandma talked me into going to the attorney’s office with her, so I did. I was 11 years old.

Grandma told me the story of how she met Grandpa in the old country. He had come to visit Grandma’s parents for some reason or other. She saw him, and he saw her. The next time she saw him was when he returned to ask her father for her hand in marriage.

I was told the story of how Grandma came to Logan. After they were married, Grandpa had come to America to find work. After he left Hungary, Grandma found out that she was pregnant with Paul. Later Grandpa sent for them. When Paul, who was about two years old, got off the train, Grandpa took one look and said, “That’s my son.”

Grandpa used to read his Hungarian papers after dinner and before bedtime. I remember him reading out loud to Grandma with tears in his eyes, saying, “My poor country. My poor people.” He was referring to Hungary, as it was being taken over my communism. Sometime he’d fall asleep at the table while reading his papers. He’d get upset when Grandma would call for him to come to bed.

Grandpa didn’t drink to speak of, but in his later years he would have half a shot of port before he cleaned up after work. He said that at his age, it helped his blood function after a hard day’s work. He would go downtown to the moves every Sunday. He would walk down the track, catch a bus, go to Logan to the movie, then catch the bus and walk back up the track home. Grandma used to say that he just went there to sleep. He would joke back that it was true.

After Grandpa lost most of his hearing Grandma tried and tried to talk him into getting a hearing aid. But he was too proud to let people see him wearing a hearing aid. Grandma would tell him that friends of theirs had seen him downtown and spoke to him and he wouldn’t answer. He was more ashamed of wearing a hearing aid than of people thinking that he was becoming stuck up.

Grandma surprised me with a ring for my tenth birthday. She had bought it at Logan Jewelry. It had a diamond chip as its setting. I still have it today. After I grew up and would come back to visit, Grandpa would give me money and tell me not to tell Grandma. Grandma would give me money and tell me not to tell Grandpa. It was a game that they would play with me.

And every time I went home, Grandma would ask me to make jello. She loved jello. I tried to teach her the simple instructions, but she just would not make if for herself. She wanted me to. And every time, she would stand outside of the house as we drove away and cry. It made me feel so bad.

I used to have nightmares all through my teens of Grandma dying. I would wake up crying and shaking. When we received word that she had passed away, we did not have the money it would take to go back to the funeral. I honestly did not want to, anyway, I wanted to remember her as she was when she was alive.

It was the same when Grandpa died. I think of him in death, and it’s awful. It’s easier to remember both of them in life, full of love and humor. They were such good people.

This article is adapted from a much longer account the author originally prepared for the benefit of her relatives. We thank other members of the extended Zekany, Lovejoy and McGraw families for their cooperation in preparing the final version. — ed.

Admin note: There seems to be an error in the above story. The author said that she attended the Midelburg Addition School. To my knowledge, there was no school by this name in Henlawson.

*Thanks to Bob Piros for contributing the magazine containing this article.

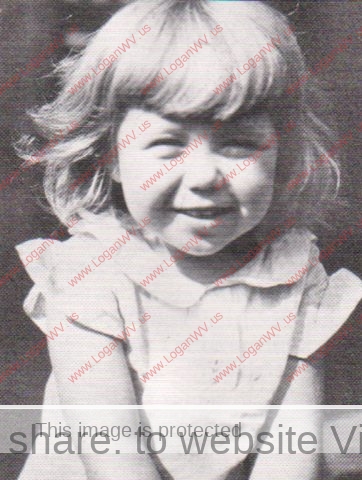

The Zekany Family Photos

Folktale Collection

The Hungarian folk stories that Donna Jean Rittenhouse recalls from her Logan County childhood were among many told by immigrant families that came to West Virginia and went to work in the mines. These new arrivals brought their culture with them from countries such as Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Poland, Yugoslavia, Italy, Ireland, Austria and Russia.

Ethnic pockets, each with a heritage and nationality of its own, took root in the coal camps and larger towns of the day. Transplanted culture provided great comfort to the homesick families. The old stories and folktales were import to survival in a new land, and they have contributed greatly to the cultural richness of our state.

The late Ruth Ann Musick preserved many of these folk stories in her book, Green Hills of Magic: West Virginia Folktales from Europe, now in its second edition. Dr. Musick was first introduced to West Virginia in the 1940’s when she became a professor at Fairmont State College. She wrote that the Mountain State seemed “a land of magic.” She would spend the next 20-odd years collecting ethnic folktales and ghost stories from the people who populated the hills around her. Dr. Musick first published two collections of Appalachian ghost tales, The Telltale Lilac Bush and Coffin Hollow, along with a book on West Virginia ballads and folk songs. Green Hills followed in 1970, a collection of 79 narratives first published by the University Press of Kentucky.

Judy Byers, a professor at Fairmont State College and Dr. Musick’s literary executor, wrote the foreword for the second edition. Byers also joined fellow storytellers Noel Tenney and John Randolph to record selected tales from Green Hills. The result is a cassette packed with tales of death and the devil, vampires, werewolves, and leprechauns, among the 12 readings. Byers hopes that the reprint of Green Hills and its cassette version will further the study and appreciation of the varied traditions of Appalachian coal miner — traditions that have continued for a century and more in the hills of West Virginia.

Green Hills of Magic is a 312-page paperback book with notes, indexes and bibliography. The new edition was issued by McClain Printing Company, 212 Main Street, Parsons, WV 26287. It is available by mail order from McClain for $9.95, plus $1.50 postage and handling, or in bookstores. The cassette tape, “Selected Stories from Green hills of Magic,” may be ordered from The Hill Lorists, P. O. Box 8, Tallmansville, WV 26237. The cost for the 60-minute recording is $10, plus $3 for 4th class shipping or $4 for first class. West Virginia residents should add 6% sales tax for both items.

Hello Judy, do you have any photos of the Venci family when they lived in Mt.Gay that you can send to this Logan site? Also would you consider writing the Venci family history and share the family stories? Lots of people might enjoy reading them.

My Grandfather Paul Dunch was born in Henlawson. I believe he is the same featured in the story. I’ve been looking for more information on his family. I’m glad I came across this article.

Wiki Tree shows the family name online.

Hi Cassandra, your grandpa Paul, is my Great Uncle Paul, which would make us 3rd cousins. We are the ones he would visit in WV all the time. Any info you want about the family I can tell you as much as I know. I still live here, with my husband. Also my mom is still living. She is your Grandpa’s niece she is 87 years young.

Your Dad Danny is my 2nd cousin. I was sorry to hear of his passing. He visited some when he was younger. The last time I remember him being here, would have been when my Grandma Mary passed I was 16 at the time. She is your grandpa’s sister. She died April 16, 1989. You can friend me on Facebook if you like.

Would love to get to know you and help you as much as I can with the family tree.

Your cousin, Debbie Rose

I loved reading this. My family is also Hungarian and lived in Logan Co. Csjagi but they changed their name to Sharkey. I keep meaning to upload some of my pictures, along with several LHS yearbooks from the 30s and 40s that aren’t here already.

I loved the story very much

I went to school with a Marie Zekany and was wondering if this was her Hungarian family.

Many thanks for this wonderful account of childhood memories. My father, raised in Monaville, always told me warm stories about the Hungarian families he knew growing up. His favorite food for all of his 92 years was always Hungarian food. I really enjoyed reading this. Many thanks. ~Carla Haslam Herkner

Carla, so glad that you enjoyed this story.

It would wonderful if you would share some of

your father’s stories about the Hungarian families

that he knew. What were some of their names?

There also is a lack of stories about the families

from Italy who lived in Mt.Gay WV.

Maybe you know about them, Joseph Scaramuzzino

known as S.Joe, Tony Piccirillo & Frank Venci.

They all had stores in Mt.Gay.

Maybe the Logan Banner wrote stories about them

& someone needs to check the newspaper files &

bring those stories out.

Frank Venci was my husband’s grandfather! My mother-in-law, Clara never stopped telling stories of Mt Gay and Logan, WV!!

Thanks to Franklin Thompson for all of his

hard work in putting this story on this website.

Thanks to all of you who viewed & shared the

story on Facebook.

Hope to see more people sharing their family stories

on this site.