By Keith Gibson

In 1972, at the age of 22, I completed a twelve-week mining course at Sharples and graduated with a 95 % average. As much as I tried though, I couldn’t get anyone to hire me because of no underground experience. The Pittston mining office was almost directly across the river from our house, so I took advantage of being so close and dropped by every other day. I’m sure that “Red Herndon,” the H.R. man got sick of me coming in every other day asking for a job. We even got to where we were on a “first name” basis. I’d walk in and say: “You got anything today, Red?”…….He’d answer: “Nope, no job opening today Keith, sorry.” Even though I knew at the time you always have a better chance of getting a job if you know somebody that has connections, the thought never occurred to me. A few days later I was talking to my father-in-law and mentioned that I was trying to get a job in the coal mines but having no luck He said: “Why didn’t you tell me you wanted a job in the mines?” “Give me a couple of days to work on it.” Two or three days later Rhonda and I went to Man to visit her mom and while we were there her dad walked in and said: “Hey “Wolfman,” ( a nickname he gave me because of my long hair) you still want a job in the mines?” I said: “absolutely.” He said: “Go to the mine office in the morning and tell Red I said to give you a job.” The next morning when I went to the mine office Red shook his head and said: “Why didn’t you tell me you were Bill Watkins son-in-law?” I said: “You didn’t ask!” He just shook his head some more and wrote something on a piece of paper, folded it and put it in an envelope. “Here, take this to Ken Fraley, the superintendent at Wade #1 coal mine on top of the mountain at Taplin. I don’t know what was on the paper but when I got there he looked at it and said: “Can you start in the morning?” At the time, I was working as a welder/fabricator in a machine shop at Chauncey, doing metalwork and helping rebuild mining equipment. I asked Mr. Fraley if I could start two days later because I had to quit my job and pick up all of my tools. He said sure, not a problem. I’ll see you in a couple of days.

A couple of days later a boss, and another new employee and I were installing 10′ sections of 2” steel water line from the top of the mountain to the bottom, and sometimes it was so steep that the section of pipe you had would get away from you and shoot down the side of the mountain, disappearing into the trees and bushes. Everything was working out great though, now I was going to be making more money, working at a union coal mine, going from my old wage of $2.90 an hour to $5.43 an hour, and on top of that, our daughter was due to be born in two more months. The next two months went by quick and our beautiful daughter arrived on July 4 and I thought “WOW,” I’m a daddy. Man, I was one proud papa, and even took cigars to all the guys I worked with. But it wasn’t very long before I found out that there was more to being a daddy than what I thought, like helping mommy when she had to get up different hours of the night because the baby had colic. Or changing a diaper. I always bucked when it came to changing a diaper. I don’t like surprises!! Now, if the baby had did a #1, no problem. But if she did a #2 I always turned it over to momma. But the realization of being a dad didn’t really hit me until our daughter was learning to talk and one day she looked up at me with those big beautiful eyes and said “da da”……Well, the tough coal miner, with tears in his eyes, melted like butter on a hot stove, and I’m thinking, “how can I get the moon for this kid?? “I guess she’s a little young for a new car!!” Yeah, I was wrapped.

When I took the twelve-week mining course the biggest part of it took place inside of a classroom at Sharples, WV, learning about mining laws, studying mine maps, and learning to ventilate a coal mine. The last week of class was spent on a big flat piece of property playing with different pieces of mining equipment learning how they operate. There’s quite a difference between this and actually going several miles under a mountain. Many coal miners have worked in coal seams that were thirty inches high or even less, but the seam of coal at Wade #1 was called the “Coalburg” seam, and it started out at twelve feet. You didn’t have to bend over to go back in this coal mine, in fact if you wanted you could jump up and down. Some of the old-timers that were used to working in low seams of coal and had many years of underground experience didn’t like the height. They said there was no way you could “sound the top”, meaning you couldn’t reach the roof of the mine to hit it with a hammer to see if it made a hollow sound or not. If a miner hit the roof of the mine with a hammer and it sounded solid he knew the top was good and it probably wouldn’t fall in, but if it made a hollow sound he knew it needed extra support and to avoid it as much as possible.

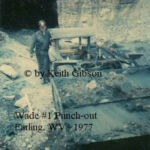

The method used to mine the coal at Wade #1 was called “the conventional method”. A “conventional” section didn’t have a Continuous Miner (a machine that literally rips the coal right out of the seam and loads it into a shuttle car). On a conventional section we had to drill and “shoot” the coal so a loading machine could load it into a shuttle car, and after a few years of underground experience, I took the test and became a certified shot fireman. On a conventional section coal was usually removed eight to ten feet at a time. This was referred to as a “cut of coal,” and before a shot fireman could use explosives to turn the solid coal into small lumps a number of jobs, performed in a certain order, had to be accomplished. When the “cut” of coal was loaded into shuttle cars, it left eight to ten feet of unsupported roof that had to be supported or made “safe before anyone was allowed to go under it. Anyone that goes under unsupported roof in a coal mine not only breaks federal and state laws, but also puts himself in danger of being covered up in a roof fall. First, the Roof Bolting operator goes in and sets temporary roof supports, drills holes in the roof, and then install hardened steel bolts that are anywhere from three feet long up to ten feet long (depending on the condition of the roof) to tie the strata together to keep it from falling. Next a Cutting Machine Operator would take a 15 RB Joy Cutting Machine, which resembled a giant chain saw on wheels, and cut an 18 to a 24-inch gap at the bottom of the seam, and then raise the cutter bar up a little and do it again widening the gap to roughly 2 1/2 feet. He would then angle the cutter bar and drag out any loose coal that may be under the seam. After this, he would rotate the cutter bar and cut a vertical gap on the right side from the roof to the floor. Now when the explosives were detonated (or “shot”) the coal had somewhere to go. It would blow forward; toward the gap on the right, and toward the gap at the bottom. But you couldn’t “shoot” the coal until a drill man came in and drilled holes in the seam to put the explosives in. After the holes were drilled, the shot fireman would push the explosives back into each hole, insert a clay “dummy” and tamp it with a tamping stick to keep the force of the explosion from shooting out the hole. Then he would wire all the explosives in series, attach a 50 ft. cable, go around the next corner, yell “FIRE IN THE HOLE” three times and detonate the explosives. The results were a pile of lump coal that could be loaded into a 15 SC shuttle car using a 14 BU 10 Joy loading machine. When the loader man got the cut of coal all cleaned up he would move over to the next entry, or tunnel (one of six), and begin loading the coal out of that entry, and the sequence of events would start all over again in the entry he just left. Over the years I had always heard coal miners refer to each other as “brothers.” I never thought much about it, but it didn’t take long to understand what they meant.

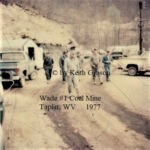

Working At Wade #1

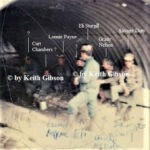

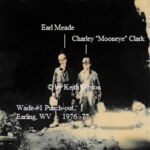

It’s a whole different world underground, and it isn’t very long until a bond is created. When a crew of coal miners works together 8 to 10 hours a day five to six days a week under a mountain they become more like family and begin watching out for each other, and just like a family, sometimes we would get into arguments, even to the point of fighting, which was ok, but if an outsider started any trouble with one of us he had the whole crew to fight.I started out as a “Red Hat,” or inexperienced miner back in the spring of 1974, but it wasn’t long before I was “one of the guys,” in fact I was tagged with the nickname “Cheetah”. The guys that worked at Wade #1 made it sound more like a “zoo” than a”crew.” I was known as “Cheetah, the monkey man.” And then there was “Moon Eye,” “Frogman,””Sly Fox,” “Country,” “Harts Creek,” “Gonzo,” “Sarge”, and “Ernie” (his real name). Two other guys I’ll never forget is Grady Nelson, and his son Danny. Also Eli Sturgill, Savage Duty, Curt Chambers, Sherwood Queen, and many more guys that were part of our family. When you’re a “red hat” in the coal mines you always get the job nobody else wants. My first job consisted of hanging curtains to direct the airflow so we could have fresh air to breathe, but just as important, to rid the mine of any methane gas and coal dust that was hanging around in the air to avoid a mine explosion. Since the coal seam was so high, the curtains (which was made out of a canvas-like material) had to be BIG curtains, something like 15’x30′. You have to hang these curtains from wooden “fly boards” and “half-header boards” that the roof bolting crew had bolted to the roof of the mine. I had to use a 10 ft step ladder and a hammer and nails, but it wasn’t too bad of a job, unless the curtain got caked with mud and slop, and felt like it weighed 500 pounds, which was most of the time. I learned quickly to wash off the mud with a water hose and I got really good running up the 10 ft. step ladder with a claw hammer in one hand, the end of a curtain in the other hand, and nails in my pocket, acting like a monkey, which of course is how I got the nickname “Cheetah”.

Like most jobs, in the coal mines you start at the bottom and work your way up to a better job and a higher wage. In no time at all I was sick of being a “ventilation man” so I went to MSHA (Mine Safety & Health Administration), passed the required test, and became a “certified” shot fireman, which brings to mind the time we were cutting a “breakthrough'” (or “cross-cut). After you advance the entries, or tunnels, to a certain point you have to cut a crosscut from one entry to the other. The mining procedure is the same, but instead of going forward you’re now turning left until you “breakthrough” to the other entry. The memory it brings to mind was when we were mining “breakthroughs” and the “spad men” got our spads off-center.

Engineers, or “spad men” use a transit to mark the roof of the main entries with spads, which enables the section boss to locate and mark the “true” center of each entry so the entries won’t veer to the left or right, but will run parallel and stay the same distance apart, and it always took the same amount of “cuts” for each crosscut to “break-through” into the next entry, with crosscuts going from #6 entry to #5, #5 entry to #4 and so on, all the way over to #1. One evening, not knowing that #5 entry had veered to the left and was closer to #4 entry than we realized (because the spads were off), I loaded and tamped #5 crosscut and was ready to detonate the explosives. I wired all the explosives in series, attached the cable and went out around the corner out of the blast zone. According to mining law, I looked around to make sure no one was in the line of fire, yelled “Fire in the hole” three times, and detonated the explosives.

You would have to be there to realize the magnitude and force of the explosion when I “shot” a cut of coal down at Wade #1. When I first became a certified shot fireman I was loading 16 holes. Five sticks of explosives with a blasting cap tamped tight with 2 clay dummies in each hole. A total of 80 sticks and 16 blasting caps detonating almost at the same time. The 4 holes across the bottom of the seam of coal had #1 blasting caps in them. The second row had #2 blasting caps, the third had #3, with #4 caps across the top row. Each row detonated milliseconds apart allowing room for each explosion. Which was pretty big.

The next thing I knew our section boss came running out of #4 entry cussing every breath. I’m sure you’ve heard about people being in the wrong place at the wrong time. Well, our boss was definitely in the wrong place at the wrong time. We had no idea that #5 crosscut was close to blowing through to #4 when I detonated the explosives. And the bad part was our boss was up in #4 main entry marking the coal seam (so the entries would stay straight). When the explosion went off, it had partially shot through and scared the crap out of him, peppering him with small pieces of coal. After he calmed down and realized he was still in one piece with no broken bones, we came to the conclusion that the center spads had to be off. After an investigation, it was determined that they WERE off and #5 entry was driving left of the center line and was dangerously close to #4 entry. In fact, it was the fourth cut that shot through when it should have shot through on the fifth cut. The main entries were seventy feet apart, center to center, and each cut was eight feet deep, so it should have taken five to five and one-half cuts to put the crosscut through. It only took three.

To say that working underground is dangerous is an understatement, but you get used to it. If you stop and think about it, driving down the road is dangerous, because you never know what the other guy is going to do. At least you have some control when you work underground, by working as safe as you can, and not taking any chances.

My dad worked in the mines for thirty years. When he first went in the mines coal miners had to hand load the coal with shovels. Growing up in the mechanized age of coal mining, I can’t imagine what it was like to have to hand load coal for a living. One night while I was working on the beltline at Powellton #1, a coal mine, at Lorado WV, I thought of the old song by Tennessee Ernie Ford about “loading 16 tons of coal”. I didn’t know how much coal one man could hand load back in those days, but I did wonder how long it would take 16 tons of coal to go by me on the beltline, so I walked out to the stacker belt where the coal is measured in tons as it goes by. I looked at my watch and timed the coal as it went by and saw 16 ton go by me in less than thirty seconds. A big difference between then and now.

My dad was a life long coal miner in Logan Co Reading your story really brought me back to his time, his tales and warms my heart. Marvin Pelfrey was my dad.

Thank you for your comment. So glad you enjoyed the story.

My name is tommy Perry from Gilbert o Justice. I am 82 years old and I remember my dad Walter Perry hand loading 30 inch coal.. He came home Black and wet most of the time. This was in the 40’s and 50’s. He was 5’6 and weighed 145 pounds. I swear he was one of the strongest men in that area. I could not believe his strength. In the 60’s He was put on the Joy loader. He said it was fun to operate, compared to hand loading. He told me that he did not want me to work in the mines because he had no hearing in one ear due to an explosion. He was also in a slate fall. He had his back broken in 1957 and went back to work in about 3 months. He was saved from death being a small man on the loader that the slate was pinned in the cubby hole where the operator sat. I graduated in 1957 and joined the army in Williamson.

and spent 3 years in Germany. I got out and was about to apply for a job but in the early 60’s not much work was going on. Caught a train to Wash D C and found work in sales for 45 years. I love the coal miners and the work ethic my dad instilled in me He died in 1999 from Alzheime’ss disease.PS I learned more from your article than I ever knew before. Also, Sherwood Queen is my first cousin.

Thank you very much for your comment. It’s great to hear from one of the cousins of someone I worked with at Wade #1. It’s been a very long time since I’ve seen Sherwood but I’m sure he’s still the great person he was when we worked together at Wade #1. You probably know the section boss I mentioned in the article. Conrad Cline was a good boss. He was good to his men and knew how to mine coal. He didn’t try to tell us how to do our jobs, he knew that we knew what we were doing and left us alone, unless we needed him, and he was always there if we did. There were a few section bosses at Wade that came and went, but I think Conrad got more coal mined than any of them. I’m glad you enjoyed the article. God bless you. Take care of yourself. K. Gibson

Some of the guys I worked with back in the 1970’s, that’s mentioned in the above article, have passed on; but they will forever remain a part of the wonderful memories I have that happened 40 years ago.

I remember as a kid seeing the coal bank back when I played in the mountains in the 1950’s. But it was just the other day when it struck me to take pictures so some of our history could be preserved. I think we can never truly realize the many problems that the pioneers of Logan, (West) Virginia had to overcome just to survive.

Keith,

You’ve done a good job giving a brief description of underground coal mining (an activity that is far more complicated than most people understand). And, you have acknowledged the comradery, friendships and inter-dependency that underground coal miners form with each other.

Without using a map or drawing, it is very difficult to explain the layout of a mine, and in particular, a typical production section and the co-ordination of equipment movements, ventilation, sequencing of specific tasks and activities.

Perhaps the most complicated activity is the “cable handling” necessary to allow several pieces of equipment with their “extension cord” trailing cables to move about without interference with each other.

It is a pleasure to see examples of the “language” of the underground coal miner, the words and names they use in the practice of their trade.

You inadvertently mentioned that the entries were driven on 40-foot centers when it appears that the coal left between entries is 40 feet wide.

Thanks for your efforts and I look forward to more from you.

.

P.S. As my Dad would say: “Every now and then, lets stop and do some rockdusting!”

Hey Doug, thanks for the comment. If I remember correctly the centers were 40 feet at Wade #1. Of course, this left pillars of coal to help hold the top up. It was when we began “pulling pillars” that it really got interesting (and scary). I believe it’s called “Retreat Mining.” As you probably already know, that’s when you back up and take ALL the coal as you go, which removes the support, and you have “controlled” (as much as possible) roof falls. I remember one time at Wade #1 when we had pulled back almost 6 ‘break throughs” (or cross cuts) before it finally fell. When 5 or 6 “break throughs” fall at the same time, especially in a 12 ft. seam of coal, it creates a wind that will almost knock you down. And as far as “Rock Dusting”……… every time I run into some of my old buddies I used to work with, we always stand around and talk about back when we worked together, and reminisce about “Running Coal.” After we had stood there and “Run Coal,” (so to speak) for a while one of the guys said, “Guys, if we keep standing here “Running Coal” we’re gonna have to “Rock Dust” in a little bit!!

Thank you for sharing! We who have not done coal mining have no idea of what is involved.

Thank you for your comment, I appreciate you reading the article. And yes, a person would have to be there to really know what it’s like. Ask any miner and he will agree, It’s a whole different world when you’re 4 or 5 miles under a mountain.